The beginning of the philosophical path

Even in adolescence, Jung began to deny the religious ideas of his own environment. Sanctified moralizing, dogmatism, the transformation of Jesus into a preacher of Victorian morality - all this caused him genuine indignation. According to Karl, in the church everyone shamelessly talked about God, his actions and aspirations, profaning all sacred things with hackneyed sentimentality.

It is worth noting that the essence of Jung's philosophy could be traced back to his early years. Thus, in Protestant religious ceremonies, the young philosopher did not notice a trace of the presence of God. He believed that God once lived in Protestantism, but had long since left the corresponding churches. He became acquainted with dogmatic works. This is what led Jung to think that they could be considered “exemplars of rare stupidity, whose sole purpose is to conceal the truth.” The young Carl Gustav held the view that living religious practice stands far above all dogma

Notes

- ↑ 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Jung K. G.

Tavistock lectures. Analytical psychology: its theory and practice / trans. from English V. I. Menzhulina. - M: AST, 2009. - 252 p. - Jung K. G.

Symbols of transformation. - M.: AST, 2008. - 736 p. - Jung K. G.

Archetype and symbol. - M., 1991. - 304 p. - Jung K. G.

Psychology of transference. Articles: per. from English — M.: Refl-book; Kyiv: Wakler, 1997. - Jung K. G.

The structure of the psyche and the process of individuation. - M., 1966.

Jung's Dreams

There is also mysticism in Jung's philosophy. In his dreams of that time, one motive played the utmost importance. So, he observed the image of an old man endowed with magical powers, who was considered like his alter ego. A timid and rather reserved young man, personality number one, spent his life in everyday life. In dreams, another hypostasis of his “I” appeared - this is personality number two, who even had his own name (Philemon).

Summing up the results of his studies at the gymnasium, Carl Gustav Jung read “Thus Spoke Zarathustra,” after which he became seriously frightened: Nietzsche also had “personality number 2,” which Zarathustra called. However, she managed to supplant the personality of the philosopher himself (by the way, hence Nietzsche’s madness; this is exactly what Jung believed, despite the extremely reliable diagnosis made by doctors). It is worth noting that the fear of similar consequences of “dreaming” contributed to a decisive, confident and rather rapid turn into reality. In addition, Jung had a need to study at the university and work at the same time. He knew that he needed to rely solely on his own strength. It was precisely such thoughts that gradually led Karl away from the magical world of dreams.

Somewhat later, Jung’s teaching about two types of thinking also reflected the personal experience of dreams. The main goal of Jungian psychotherapy and Jungian philosophy is nothing less than the unity of the “inner” and “outer” man. It should be added that the thoughts of a mature philosopher regarding religion, to one degree or another, became only the development of those moments that he experienced in his childhood.

Explanatory note

School of the outstanding Swiss psychologist K.G. Jung is an integral part of modern psychoanalysis. Concept by K.G. Jung embraces personality in the unity of conscious and unconscious aspects, individual-personal and collective-archetypal. It not only has enormous theoretical value, having influenced almost all modern humanities, but has also proven its effectiveness in more than half a century of clinical practice. It has been used in applications both to psychoanalytic treatment of adults and to child psychotherapy and psychocorrection. It is used both in long-term therapy and analysis, and in short-term counseling. Jung's approach combines rational and emotional-imaginative elements in psychological practice, placing special emphasis on the development of imagination and creativity. Being an exact science in the strict sense, analytical psychology does not become a dogmatic discipline, but represents a wide dynamic field of research where the most progressive trends of modern humanitarian thought come into contact. Widely recognized throughout the world, Jung's concept of individuation - personality development - thus today has both a carefully developed theoretical basis and a rich arsenal of highly effective methods of psychotherapy.

The main goal of the discipline “Analytical Psychology K.G. Jung" is to familiarize students with Jungian methods of psychotherapy.

Objectives of the discipline “Analytical psychology K.G. Cabin boy":

- introduce students to the history and theory of analytical psychology;

- show the contribution of C. G. Jung and Jungian analysts to modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy;

- show the possibilities of using Jungian concepts in applied psychoanalysis;

- introduce the basic methods of Jungian analysis.

The knowledge gained as a result of mastering this course can be used for psychotherapy, individual, family or business counseling, psychological and pedagogical work, psychocorrectional classes with children, and applied psychoanalysis.

A distinctive feature of the course is a combination of lectures and practical classes, in which, with the help of demonstrations, exercises and video materials, students will be able to master both classical and original author's psychotherapeutic methods developed within the Jungian school.

As a result of studying the discipline, students will know:

- the story of K.G. Jung and analytical psychology;

- basic concepts of analytical psychology;

- contribution by K.G. Jung and his followers in modern psychoanalysis and psychotherapy;

- applied use of K.G.'s ideas Jung in various contexts;

- general methodology of Jungian analysis;

- principles of Jungian work with dreams;

- special techniques of Jungian analysis for different types of psychotherapy;

As a result of studying the discipline, students will be able to:

- apply the ideas of C. G. Jung and his followers in psychotherapy;

- apply the ideas of C. G. Jung and his followers in applied psychoanalysis;

- work with dreams in psychological practice;

- use active imagination methods;

- use tests of Jungian personality typology.

The author's distinctive feature of the course is the emphasis on the application of the ideas and methods of C. G. Jung to the most pressing issues of modern life. New technologies (audio and video materials) are actively used in teaching.

Sources of teachings

When determining the sources of Jung's philosophical ideas and certain teachings, it is customary to overuse the word “influence.” Naturally, in this case, influence does not mean “to influence” in the literal sense of the word when talking about great theological or philosophical teachings. After all, you can only influence someone who represents something. Carl Gustav's development was primarily based on Protestant theology. At the same time, he assimilated the spiritual atmosphere of his own time.

Jung's philosophy belongs to German culture. This culture has long been characterized by an interest in the “other, night side” of existence. Thus, at the beginning of the last century, the great romantics turned to folk tales, “Rhine mysticism,” the mythology of Tauler and Eckhart, as well as Boehme’s alchemical theology. It is worth noting that before this, Schellingian doctors had already tried to use the philosophy of the unconscious of Freud and Jung in treating patients.

Past and present

Before the eyes of Carl Gustav, the patriarchal way of life in Germany and Switzerland was breaking down: the world of castles, villages, and small towns was leaving. As T. Mann noted, directly in their atmosphere there remained “something from the spiritual component of the people who lived in the last decades of the 15th century.” These words were spoken with an underlying spiritual predisposition towards madness and fanaticism.

In Jung's philosophy, modernity and the spiritual tradition of the past, natural science and alchemy of the 15th–16th centuries, scientific skepticism and Gnosticism collide. Interest in the deep past as a category that constantly accompanies society today, preserved and affecting us to this day, was characteristic of Jung even in his youth. It is worth noting that at the university, Karl most of all wanted to study as an archaeologist. The fact is that “Depth Psychology” in its methodology somehow reminded him of archeology.

It is known that Freud also several times compared psychoanalysis with this science, after which he regretted that the name “archeology” was still assigned to the search for cultural monuments, and not to “spiritual excavations.” "Archae" is the first principle. Thus, “depth psychology”, which removes layer after layer, gradually moves towards the roots of consciousness.

It should be noted that in Basel archeology was not taught to students, however, Karl could not study at another university: he received a small scholarship only in his hometown. Currently, the demand for graduates of the humanities and natural sciences of this university is quite high, but at the end of the last century the situation was the opposite. Only financially wealthy people had the opportunity to study science professionally. The law, medicine and theology faculties also guaranteed a piece of bread.

A specific approach to science

For whom are all these old books published? Science was a useful tool at that time. It was valued solely for its applications, as well as for its effective use in construction, industry, medicine and commerce. Basel was rooted in the deep past, and Zurich was heading into an equally distant future. Carl Gustav noticed in such a situation a “split” of the European soul. According to Jung's philosophy, industrial-technical civilization consigned its roots to oblivion, and this was a natural phenomenon, since the soul became ossified in dogmatic theology. As the famous philosopher believed, religion and science came into conflict for the reason that the first was to some extent detached from life experience, and the second avoided truly significant problems - it adhered to pragmatism and carnal empiricism. Jung's philosophical view of this will soon emerge: "We have become rich in knowledge, but poor in wisdom." In the picture of the world that is created by science, man is only a mechanism among other similar ones. Thus, his life loses all meaning.

That is why there is a need to identify the area where science and religion do not refute each other, but cooperate in search of the roots of all meanings. Psychology soon became a science of sciences for Carl Gustav. From his point of view, it was she who was capable of giving the modern individual a holistic worldview.

Searching for the “inner man”

Jung's philosophy briefly and clearly suggests that Carl Gustav was not alone in his search for the “inner man.” Many thinkers of the late 19th and early 20th centuries had the same negative attitude towards the church, the dead cosmos of natural science, and even religion. Some of them, for example, Tolstoy, Berdyaev or Unamuno, turned to Christianity and gave it a very unorthodox interpretation. The rest, having experienced a crisis of the soul, began to create philosophical teachings.

By the way, it was not without reason that they called these trends “irrationalist.” This is how Bergson's intuitionism and James's pragmatism emerged. Neither the evolution of nature, nor the world of human experience, nor the behavior of this primitive organism can be explained through the laws of physiology and mechanics. Life is a Heraclitean stream; eternal becoming; "impulse" that does not recognize the law of identity. The cycle of substances in the natural environment, the eternal sleep of the material, the peaks of spiritual life - these are just the poles of an unstoppable flow.

In addition to the philosophical significance of Jung's analytical psychology as a “philosophy of life,” it is important to consider the fashion for occultism, which certainly affected him. For 2 years, the philosopher participated in spiritualistic seances. Carl Gustav became acquainted with many literary works on numerology, astrology and other “secret” sciences. Such student hobbies largely determined the features of Karl’s later research. The philosopher soon abandoned the belief that mediums establish communication with the spirits of the dead. By the way, the very fact of such contact is denied by occultists.

ANALYTICAL PSYCHOLOGY OF C. JUNG

Strictly speaking, from the position of Freud himself and his orthodox followers, only classical psychoanalysis according to Freud can be called psychoanalysis. Therefore, many dispute the right to classify Carl Gustav Jung (1875-1961) and the psychoanalytic direction he developed as psychoanalysis and call it analytical

,

deep

,

psychology

.

Carl Jung was one of the first, most talented and most beloved students of Sigmund Freud, and even, at the suggestion of Freud himself, was chosen as the first president of the International Psychoanalytic Association.

However, after the first years of admiration for Freud (who really opened up vast new horizons of psychology and psychotherapy, which Jung did not deny subsequently) and unconditional adherence to his theory and practice. Jung begins to increasingly show independence, which was never encouraged by Freud (in the sense of interpreting and conducting psychoanalysis) and “psychoanalytic freethinking.”

On the one hand, he questioned some of the basic provisions of classical psychoanalysis (considering the role of the sexual instinct to be exaggerated, although important; the role of the early childhood period to explain the causes of character formation, neuroses and various psychological problems of adults) was exaggerated, although important) , considered it possible to deviate from Freud’s scrupulously precise instructions for carrying out certain technical techniques.

On the other hand, he “dared” to independently expand the scope of psychoanalysis far beyond the framework of classical Freudianism, including the study and interpretation of mythology, various, primarily Eastern, religions and cult rituals, and even parapsychology and alchemy, which was completely unacceptable for Freud , who considered himself a consistent materialist. Freud always emphasized his atheism, considering religion a mass neurosis (which did not prevent subsequent theologians from trying to combine Freudianism as a fashionable trend that attracted the intelligentsia with religion), and Jung was always a believer.

All this served as the basis for the “excommunication of the apostate” from classical psychoanalysis, but not only did not diminish the authority of C. Jung and his teachings, but made him the undisputed leader in the new psychoanalytic branch, and, in the opinion of many, in the independent scientific and practical direction, which called “depth psychology”.

This was a gratifying case for science when a dispute between two great scientists and their schools did not diminish the authority of either of them. Each retained and grew a large number of sincere adherents, propagandists and followers.

Each of these psychoanalytic directions - Freud's psychoanalysis and Jung's depth psychology - served as an impetus for the further development of the theory and practice of modern psychology and psychotherapy and brought not only interesting theoretical findings, but also practical benefits to specific people in overcoming neuroses and solving personal and interpersonal psychological problems.

Jung's analytical psychology, no less than Freud's psychoanalysis, has become an integral feature of modern public culture, influencing not only psychotherapeutic theory and practice, but also the arts, sciences and other spheres of life of modern society.

Carl Jung was the first to introduce the concept of “collective unconscious” into psychology, psychotherapy, and, one might say, into philosophy, while before him, Freud himself and all supporters of psychoanalysis always talked only about the individual unconscious.

What is the “collective unconscious” according to Jung?

He believed that the individual unconscious does not exist on its own, but rather “floats” in the ocean of the collective unconscious. This is a completely logical assumption. Jung had what we call “cosmosense,” that is, an ever-present sense that in the Universe “everything is connected to everything else.”

At the same time, we put into the word “Cosmos” its original meaning, which was given to it by the ancient Greek philosophers - “the originally established Order in the Universe”, to which everything and everyone from small to great is subject, and the fact that these relationships are not always obvious does not mean that they don't exist.

Therefore, it is not only logical, but also quite “materialistic” and “dialectical” to assume that the human psyche, and therefore its unconscious part, which is no longer disputed by anyone, despite its individual uniqueness, is not isolated and is subject to influence.

At the same time, genetic influence - the transfer of certain hereditary information - is no longer disputed by anyone in our time (only the degree and nature of such hereditary influence are debated).

And from the moment Albert Einstein proclaimed the unity of space and time, it can be assumed that the influence of the collective unconscious on the individual extends not only in time (in the continuity of generations), but also in space, that is, being influenced by the modern collective unconscious surrounding us, as well as the entire surrounding world and even more so - nearby and distant societies (groups and communities of different scales).

This is confirmed by the phenomena of “infection” of people, sometimes in large masses, with certain mental states on an unconscious level, which have long been noted in human history and studied in detail by V.M. Bekhterev.

We deliberately, on the one hand, somewhat exceeded, and on the other hand, simplified in our reasoning the problems of the collective unconscious in comparison with how Carl Jung approached them. It was important for us to remove the aura of mysticism that was being forced around his teaching (which sometimes attracted him too). The interpretation of the nature and mutual influence of these connections really gives rise to many interesting hypotheses and debates, including among Jung’s followers.

Jung firmly introduced the concept of “archetypes” into the theory of the collective unconscious. To be fair, it should be noted that this term was also used by Plato, Aristotle and their followers.

At a later time, the concept of archetypes was addressed by Johann Wolfgang Goethe, who was not only a great poet and playwright, but for many years was engaged in a serious study of the development of life on Earth and collected a unique collection of plants.

Goethe's original conclusions, which in many ways did not coincide with Charles Darwin's evolutionary theory of the origin of species, which served as the basis for Rudolf Steiner to create anthroposophy and which today meet many supporters among famous scientists, require independent consideration, which is not the purpose of our work.

We only emphasize that the concept of archetypes was not introduced by Carl Jung, as some popularizers of his teaching write, but, of course, it was Jung who acquired the psychological (psychoanalytic) meaning that is given to it in depth psychology and psychotherapy.

Jung's scientific achievements were further developed in "crossing" with Freud's brilliant discovery of the most important, and often dominant role of the unconscious. Therefore, we will briefly show the “second root” (the first is the Freudian unconscious) underlying Jung’s archetypes.

Aristotle and Goethe (we name only those who made a fundamental contribution to the interpretation of archetypes) believed that in nature all its diversity did not develop (as Darwin later argued) from some one primary element of life that came from nowhere (by the way, Darwin admitted as one of the hypotheses the primary impulse of God), and each type of plant and animal life had its own archetype - an ideal model, as if the plan of an architect (Cosmos, Supreme Mind, God).

Remember, the Gospel of John begins in Russian and in a number of other translations with the phrase “In the beginning was the word.” But “logos” can be translated not only as “word”, but also as “knowledge”, “idea”.

So, perhaps, it is more correct (and from the point of view of Aristotle and Goethe this is certainly true) to translate “In the beginning there was an idea” (a plan, a plan for creating the world), and then its implementation. “...Each creature has a pair...” - isn’t this a figurative designation of archetypes of all species, which later received a certain development and change, but precisely within the limits of the idea of each species, and each species developed and improved within the limits of its archetype?

This controversial, but, in the opinion of many serious scientists, valid hypothesis certainly influenced the modification of the psychoanalytic views of Carl Jung, although he introduced a lot of fundamentally new things, namely psychological and psychoanalytic, into the concept of archetypes.

Jung's archetypes are certain common forms of mental ideas that exist among different peoples (in many cases very similar to each other) about father, mother, leader, mythological characters in tales and legends, personifying various elements and forces of good and evil. Of course, for each individual person, these tribal or national archetypes are filled with some kind of individual content, but still some common fundamental features remain and unite these human societies around themselves, their moral and moral values, are objects of admiration, hope or fear .

Jung did a tremendous amount of work studying the history, mythology, rituals and traditions of different tribes and peoples. Based on the processing of this colossal material, he was able to identify six fundamental archetypes, which have different names among different peoples, but are united by some fundamental commonality of features. Therefore, he gave names to the archetypes not according to their popular names, but according to types that reflect a certain psychological essence that clearly distinguishes them from others.

Six main archetypes: Persona, Ego, Shadow, Anima and Animus, Self

. Moreover, all these types simultaneously live in each of us, taking their place and at the same time interacting with each other in one way or another, supporting or hindering, contradicting each other.

By the term Persona, Jung means our vision, acceptance of ourselves, our character in relation to the outside world. How we behave with different people, in different places, under different circumstances. What kind of appearance do we try to convey to others? At the same time, it is important to remember that we are talking specifically about our image of ourselves in society, our appearance, behavior, and the impression we make on others.

This does not mean at all that our ideas on all these parameters are objective and others really perceive us that way. It's about what we think

that we give such an impression. This opinion of ourselves may or may not coincide with reality and the opinions of others about us.

The next important archetypal term is Ego

.

With this term Jung defines the center of our consciousness

, which (we believe) controls and directs our behavior logically and purposefully in accordance with our goals and objective circumstances.

Again, we draw your attention to the fact that this is what we think

, but this is our opinion and even confidence may, as in the previous case (with Persona), coincide or may not coincide with reality.

The shadow is also a center, but not of consciousness, but of our individual unconscious

, a focus for material that has been repressed from consciousness. It includes tendencies, desires, memories and experiences that are rejected by the individual as incompatible with him or her or contrary to social standards and ideals.

The concepts of Anima and Animus are the unconscious guidelines that are archetypal for a given people (community) and refracted through individual consciousness to what a “real” woman (Anima) and a “real” man (Animus) should correspond to (both in appearance and behavior, morality and psychology). .

expectations accepted in a given people, nation, community

(expectations of a certain type of appearance and behavior) largely give another, derived from them, type of relationship between men and women, the relationship of a man to a woman (and expectations from her of a certain type of attitude towards herself) and vice versa.

patterns are typical for a given society

(samples, models) undergo a certain transformation in individual consciousness in connection with the personal characteristics and life experience of each person, but retain the commonality of the main features for a given society, and it is from the standpoint of the relationships and traditions of society that they influence the perception of these models by each individual and to a large extent determine mental and behavioral reactions to one’s own or someone else’s deviation from the criteria accepted in a given society.

A special, central place among the archetypes identified by Jung is occupied by the so-called Self. The self, as it were, organizes and protects the integrity and orderliness of the personality.

It is here that the adaptation and coordination interaction of the unconscious and consciousness takes place, which find compromises, if possible eliminate or soften the contradictions between instinctive manifestations that are unacceptable in a given form or under given conditions, that is, they not only reconcile biological needs and social norms, but often combine their efforts .

For example, aggressiveness can be transformed into assertiveness in achieving socially acceptable and even prestigious goals: winning competitions, championship in art, business, politics, persistent self-improvement, etc.

The self has the most important task of preserving the integrity of the personality; it reconciles and coordinates consciousness and the unconscious. It is when the self fails to cope with this task that various kinds of internal conflicts, neuroses, neuropsychic deviations, complexes, breakdowns and even severe mental disorders arise.

Currently, the concepts of extraversion and introversion have firmly entered into psychology and psychotherapy, characterizing the different orientation of the personality, or more precisely, the attention, thoughts, and neuropsychic energy of a person: outward - towards external objects and actions or inward - towards self-experience, self-absorption, reflection.

As is already clear from the names themselves, the attention and activity of an extrovert is directed outward, while that of an introvert is directed into their inner world.

Naturally, and this was emphasized by Jung, “pure” extroverts and introverts cannot exist in nature. We are talking only about the predominance of a certain type of mental states and behavioral reactions.

The brightest extrovert, living an external life, periodically withdraws into himself, into his experiences and thoughts. Likewise, the most self-absorbed introvert, if he does not suffer from autism (no longer in the psychoanalytic sense of one of the defense mechanisms of neurosis, but as a classic psychiatric diagnosis of a severe mental illness), periodically switches his attention and actions to external objects.

By the way, this is where the mistake often occurs not only of “non-psychologists,” but even of some beginning psychologists, mostly first-year students. I really want to find out as a result of testing whether I or someone I know is an introvert or an extrovert. Such a categorical expectation usually leads to doubts about the validity of testing when compared with real life impressions of oneself or another person being tested.

This is absolutely normal: every extrovert will have introverted moments and reactions, as well as vice versa. Moreover, as statistics from studies conducted by American scientists on a large number of university students show, approximately one third of people have extroverted

and

introvertive signs

Such people are called

ambaverts.

A typical mistake of beginning “testologists” is an attempt to classify oneself or another as choleric, sanguine, or phlegmatic.

or

melancholic

,

left-hemisphere

or

right-hemisphere

, or one of the types of personal accentuations, which practically never occur in their pure form.

Quite often, personality traits and states are distributed fairly evenly, without the predominance of any particular type. If, nevertheless, on the basis of testing or observation, they are classified into one category or another, then it should be remembered that we are talking only about the predominance of a certain type.

At the same time, for serious analysis and, especially, practical recommendations, one should carefully analyze and take into account the degree of “involvement” in a given context of personality traits and states of other, related types and reactions.

The same “reasonable” attitude should be towards another interesting classification of people developed by K. Jung according to the type of dominance of one of four psychological functions: sensation, intuition, emotions, thinking.

Accordingly, we can talk about a sensing, intuitive, emotional and thinking type of personality.

To some extent, this observation is a precursor to the conclusions of the authors of neurolinguistic programming (NLP), which you will read later, about the predominance of one or another modality of perception in people (visual, auditory, kinesthetic, etc.).

In general, it must be said that Jung turned out to be a generator of ideas for a number of subsequent psychotherapeutic directions. Thus, according to Jung, every individual has a desire for individuation, or self-development. He uses the term “individuation” rather than individualization, giving it somewhat different content. Jung called individuation the process of forming an individual as a single, holistic personality.

Since each personality is unique, determined by a unique combination of biological (innate) and social (acquired) influences, individuation implies nothing more than a “path to oneself,” becoming one’s true self (or at least movement in this direction), that is self-realization is the process of developing integrity and, as it were, freeing the individual from the fetters that hinder his self-realization.

This is very close to what later formed the basis of humanistic therapy and especially theory of self-actualization about the inherent tendency in a person to self-development, to self-actualization, to self-realization.

Many concepts of personality integrity according to Jung have much in common with certain provisions of Gestalt psychology and Gestalt therapy. Later we will dwell in more detail on these interesting and completely independent areas.

We just want to emphasize once again that in the classical directions of psychotherapy, in a fundamental sense, there are more similarities than differences, and the influence of such outstanding scientists as Sigmund Freud and Carl Gustav Jung fed and continues to feed ideas into various psychological and psychotherapeutic directions and schools, even those , which arose, like Federick (Fritz) Perls's Gestalt therapy, based on criticism of classical psychoanalysis.

But let's return to Carl Jung in terms of the specific application of his ideas in the technique of practical psychotherapy.

The main condition for effective therapy according to C. Jung is sincere creative cooperation between the psychotherapist and the client. Moreover, this should not be cooperation between a manager and a subordinate, but equal partners solving a common problem. Only their joint efforts can bring real success.

In other words, from a client who has turned to a psychotherapist for help, not only sincerity and discipline are required, but also creative activity, a willingness, together with the psychotherapist, to search (sometimes for a long time and with periodic failures) for the true causes of neurosis or other psychological problem with which The client was unable to cope on his own.

Jung, without denying the importance of serious theoretical training, at the same time recommended not to commit oneself to too scrupulous adherence to theoretical provisions and recommendations, as well as to pedantically precise implementation of technical procedures (which Freud categorically demanded). Jung believed that this approach makes psychoanalysis too formalized and the client does not feel the living creative attitude of the psychotherapist, without which it is impossible to establish real active cooperation.

In addition, servility to theoretical schemes and scrupulously written (in classical Freudian psychoanalysis) recommendations can lead to the fact that the psychotherapist, instead of the true symptoms of neurosis, will unwittingly see those that are more consistent with classical theories, which will direct the search and subsequent therapy in the wrong or at least in a not entirely precise direction.

Jung's psychoanalytic therapy goes through two stages: analytical and synthetic, with each of these stages divided into two parts.

The first part of the analytical stage is the so-called recognition: the client, with the tactful help of the psychotherapist, tries to admit that the true causes of his neurosis or the psychological problem tormenting him were hidden, were pushed into the sphere of the unconscious, since they turned out to be unacceptable (unprestigious, shameful, humiliating) for their awareness.

The psychotherapist explains to the client that, despite these interfering feelings, it is necessary to try to identify the true reasons, no matter how humiliating they may seem, to extract them from the subconscious, otherwise they will continue their traumatic effect. It is necessary to explain to him that this is the same as turning a blind eye to the symptoms of any other disease, which in the meantime will worsen and may become incurable.

You cannot expect help from a psychotherapist, or from any other doctor, if you point him to the wrong place that actually hurts. And with psychological problems the situation is even more complicated, since we often hide not only from the doctor, but also from ourselves the true causes of the injury.

Therefore, the first difficult task is to expose “self-deception,” no matter how painful it may be for our pride. This part - "unmasking self-deception" - can take varying amounts of time. Sometimes, with the help of a psychotherapist, it is possible to get on the right track almost immediately (although it will still take time and mutual effort to specify and clarify). Sometimes self-deception does not want to give up for quite a long time, but through the efforts of the psychotherapist, who has convinced the client of the need for this difficult step, of his sincere desire to help him, and most importantly, in his readiness not only not to condemn, but to approve the courage of any (the most unprestigious in the client’s opinion) confession, — ultimately solve this first problem.

It is important to understand that recognition

- this is not yet complete clarity of the true reasons, it is the recognition that our previous reasons are self-deception, self-justification of our pride, and that together we are ready to look for and clarify the true reasons by various indirect signs, words, fantasies, dreams, actions, which sometimes at first the gaze does not have a direct connection with the problem, they seem to the client to be trifles that are not worth the attention of the psychotherapist, or funny and even indecent.

It is precisely in order to figure out what information from all this will be necessary and important for solving the problem, and the second part of the analytical stage is intended - the interpretation of the material told by the client. Many approaches of classical Freudian psychoanalysis are applied here, although, as already mentioned, without scrupulously following all procedures and prescriptions, which, according to Jung, can interfere with the establishment of an equal creative partnership between the psychotherapist and the client.

And now the first, analytical, stage is relatively completed. “Relatively” - since the analytical process is endless, and its period must be determined optimally by the psychotherapist to solve this specific problem.

Unfortunately, there are often cases when even experienced psychotherapists “dig” deeper than necessary to solve a specific problem, and, seeking more detailed (than necessary to eliminate neurosis) information, unnecessarily traumatize the patient.

The second stage of this model of analytical therapy is called synthetic by Jung.

Work (and necessarily joint work) at this stage consists mainly of teaching new models of perception of oneself and a traumatic situation and the resulting new models of behavior. Jung says that at this stage, the client, who has made (together with the psychotherapist) psychological discoveries, proceeds to implement their results in the form of new models of behavior that eliminate (or consistently reduce) past mistakes that gave rise to and aggravated psychological problems and neuroses. Such formation and consolidation of models of not only behavioral reactions, but also the perception of traumatic situations and oneself becomes nothing more than personal growth.

The second part of the second stage of analytical therapy by C. Jung is called transformation Jung characterizes this work of a psychotherapist with a client as mini-individuation, or self-learning.

During this period, the psychotherapist, remaining an equal partner of the client, gradually transfers to him (the client) more and more responsibility for his own development and independent overcoming of psychological problems.

Moreover, with the correct implementation of this process, this looks in the client’s eyes not as a gradual self-elimination of the psychotherapist, but as a growing sense of one’s own inner strength, the ability to independently cope with one’s problems, gain the courage to really look at oneself and the situation, self-confidence and master practical techniques for solving life problems. situations that previously seemed hopeless.

Jung was the first psychoanalyst to use not free associations (in accordance with Freud's categorical prescription), but so-called directed associations to identify hidden sources of neuroses in the unconscious. That is, the client did not simply let his “word creation” into the free stream of consciousness, but aimed it (also, however, without worrying about strict logic and coherence) in the direction given by the psychotherapist.

In practice this happens as follows. The psychotherapist pronounces a word, and the client begins to say whatever comes out of his mouth in response to this word, without trying to comprehend, much less specifically organize, the logical connection of his words and sentences with a given stimulus. The psychotherapist names those words that, in his opinion, can push the client’s associative verbal flow in the right (at least presumably) direction for the search.

Successful implementation of such a procedure requires special, thorough preparation and extensive practical experience of the psychotherapist. He must constantly remember that the true causes of neurosis are sometimes hidden very deeply and the removal of their defense mechanisms is often very painful.

Therefore, when choosing stimulus words, the psychotherapist, on the one hand, tries to get as close to the pain point as possible, and on the other hand, to be ready at any moment to step back or to the side, feeling that the client is not ready to expose this pain point and may (often unconsciously) hide it even deeper or (also unconsciously) protect it by blocking the path of contact with the psychotherapist.

Therefore, the procedure for the first sessions usually begins with the psychotherapist naming truly random words that have no direct connection with the problem, and then gradually narrowing the circles around the intended goal, with a readiness to quickly respond and retreat or change the direction of the search depending on responses not only verbal, but also the client’s emotional reactions.

The system for analyzing the responses received has patterns that have been refined (and refined) over many years of experience, although it is not as strictly regulated as the system for interpreting material in classical psychoanalysis by S. Freud. For example, it has been found that in most cases an associative response, given with a certain delay and an involuntary emotional reaction, shows that the word “thrown” by the psychotherapist to some extent hurt the client and the search should be conducted in this direction. In many cases, such a search, based on the principle of the children’s game “warmer, even warmer, hotter,” helps the psychotherapist quickly reach the true causes of the client’s problem than classical psychoanalysis.

Z. Freud objected to this approach, believing that directed psychoanalysis, although it speeds up the search process, can force the client to move not in the true direction, but in the direction involuntarily suggested by the psychotherapist (by the way, for the same reason, Freud refused psychoanalysis under hypnosis, believing that a hypnotized person may say not what he thinks, but what he thinks the hypnotist wants to hear from him).

Nevertheless, K. Jung’s method of directed associations is currently quite popular and has analogues not only in psychotherapy, but also, for example, in the work of an investigator with a suspect, and although here, of course, not incoherent answers are assumed, the methods of their analysis are taken into account by many discoveries of Jung and his followers.

Some authors believe that it is this idea (delay and involuntary coloring of the answer) that forms the basis of the famous lie detector.

By the way, the first technical device that records various psychophysiological reactions to correct and incorrect answers, which became famous (despite its numerous inaccuracies and errors) under the name of a lie detector, was developed in the laboratory at the Berne Cheka by the young and later famous Soviet psychologist Alexander Romanovich Luria .

Self-test questions

1. What fundamentally new did Carl Gustav Jung introduce into the psychoanalytic direction of psychology and psychotherapy?

2. How did Carl Jung disagree with Sigmund Freud?

3. What is the collective unconscious?

4. Name the main archetypes according to K. Jung and characterize them.

5. Basic psychotherapeutic approaches of K. Jung.

6. The main stages of psychotherapy according to K. Jung.

7. What is the essence of the method of directed associations?

8. Who are introverts and extroverts?

Jung's dissertation

It is worth noting that the presented observations and Jung’s philosophy, which briefly describes them, became the basis of his doctoral dissertation “On the psychology and pathology of so-called occult phenomena” (1902). It is worth noting that this work has retained scientific significance to this day. The fact is that the philosopher gave a psychiatric and psychological analysis of mediumistic trance and compared it with a darkened state of mind, hallucinations. He noted that poets, mystics, prophets, founders of religious movements and sects have similar states to those that a specialist can encounter in patients who came too close to the sacred “fire”, so much so that the psyche could not stand it - as a result, a split personality took place . Poets and prophets often add to their own a voice coming from the depths of a seemingly different personality. However, their consciousness takes possession of this content and gives it artistic and religious forms, respectively.

All sorts of deviations can be found among them, but there is an intuition that “far surpasses the conscious mind.” Thus, they capture certain “proto-forms”. Subsequently, Carl Gustav identified these ancestral forms as archetypes of the collective unconscious. Jung's archetypes in philosophy appear in human consciousness at different times. They seem to emerge regardless of human will. Proto-forms are autonomous, they are not determined by consciousness. However, archetypes can influence him. The unity of the irrational and rational, the subject-object relationship to intuitive insight - this is what distinguishes trance from adequate consciousness and brings it closer to mythological thinking. Each individual has access to the world of primordial forms in dreams, which serve as the main source of information about the mental unconscious.

The doctrine of the collective unconscious

Thus, Jung arrived at the basic concepts of the collective unconscious even before he met Freud. Their first communication took place in 1907. By that time, Carl Gustav already had a name: first of all, his fame was brought to him by the word association test, which made it possible to experimentally identify the structure of the unconscious. In the laboratory of experimental psychopathology, which was created by Carl Gustav in Burghelzi, each of the subjects was offered a list of words. The person had to react to them immediately, with the first word that came to his mind. Reaction time was recorded using a stopwatch.

After this, the test became more complicated: using different instruments, the individual’s physiological reactions to certain words, which acted as stimuli, were recorded. The main thing that was discovered was the presence of those expressions to which people did not find a quick response. In some cases, the period for selecting a reaction word was extended. Often, subjects fell silent for a long time, stuttered, “switched off,” or responded not with one word, but with a whole sentence, and so on. At the same time, people did not realize that the response to one word, which is a stimulus, for example, took them many times longer than to another.

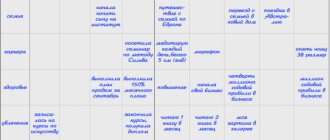

Years of creative activity

- 1983 – Carl Gustav entered the Faculty of Natural Sciences. He continued to be interested in philosophy and became interested in mystical practices. Against this background, Jung conducted spiritualistic seances. The experience gained was subsequently used in the writing of several works. The period of study became difficult due to the death of his father. There was no money in the family and Karl had to work as a tutor in between classes to support himself.

- 1900 - a young man moves to Zurich and gets a job as an assistant to the famous psychiatrist Eugene Breuler. It was this doctor who first introduced the concept of “schizophrenia.” Carl Jung settled on the hospital grounds and began writing his first works.

- 1903 - an aspiring psychiatrist marries a girl from a wealthy family.

- 1907 - Jung publishes his work “The Psychology of Dementia Precocious.” The test was sent to Sigmund Freud for review. From this moment the joint work and communication of two psychiatrists begins.

- 1909 - Carl Gustav, together with Freud, goes on a trip to the United States to give lectures. The trip brings Jung world fame and financial stability. He has the opportunity to leave his position at the hospital and go into private practice.

- 1910 - Jung returns to his homeland and devotes time to studying the question of how myths, legends and fairy tales are related to personality psychopathologies. Coldness is emerging in relations with Freud.

- 1912 - the psychiatrist publishes “Symbols and Metamorphoses. Libido". Contradictions with the founder of psychoanalysis become insurmountable.

- 1913 - Jung publishes The Red Book and Symbols of Transfiguration. Against the backdrop of Freud's rejection of the theory of the collective unconscious, their communication ceases forever.

- 1920s - a psychiatrist goes on a trip to Africa and America. He reflected his observations in his autobiographical work “Memories, Dreams and Reflections.”

- 1930 - Carl Jung becomes president of the Psychotherapeutic Society of Germany and publishes the work “Problems of the Soul of Our Time.”

- 1932 - the famous psychiatrist receives a prize in the field of literature.

- 1933-1942 _ – Jung teaches psychiatry in Zurich. During this period, he published a magazine that actively supported the Nazi ideology of racial cleansing. Each new work contains a preface, which is excerpts from the book of Adolf Hitler.

- 1944 - Jung begins teaching in Basel. That same year, a psychiatrist breaks his leg during an excursion. Trauma is followed by a heart attack.

- 1955 – Karl’s wife Emma dies. This was a great tragedy for Jung. He throws himself into his work and begins dictating his memoirs to his assistant.

- 1961 - Jung has another heart attack. After several weeks of illness, the world famous psychiatrist dies.