Delinquent behavior of adolescents Delinquent behavior of adolescents

- a system of actions that violate the rules of public order. It manifests itself in the form of disregard for moral and ethical standards (asociality), as well as criminal actions punishable under the Criminal Code (criminality). The main types of delinquent behavior are prostitution, theft, vandalism, violence, car theft, drug addiction, and participation in drug trafficking. A psychiatrist or psychologist diagnoses behavioral disorders. Examination methods – clinical, psychological. Treatment is based on cognitive-behavioral and family psychotherapy, supplemented by medication correction.

Delinquent behavior of adolescents

Delinquent behavior of adolescents

The word “delinquent” comes from the Latin language and means “misdemeanor”, “offense, fault”. The main criterion for such behavior is an antisocial illegal nature, causing harm to individuals or society as a whole. The term is widely used in social pedagogy, psychology, sociology, and criminology. There are no precise epidemiological data on the prevalence of delinquent behavior in adolescents. The frequency in the population is determined by gender and age characteristics: despite the increase in female crime, illegal and antisocial behavior is more typical for males; the age of most criminals is 14-29 years.

Signs

Signs of delinquent behavior:

- Antisocial nature of the act. A citizen commits actions that are aimed at violating the existing foundations, norms of morality and ethics in society.

- Violation of the law. The actions taken are not only antisocial, but also criminal in nature.

In addition to violating unwritten social principles, an unlawful act is also committed, entailing legal liability. - Demonstrativeness .

As a rule, actions are demonstrative in nature. When committing them, the criminal seeks to attract attention to himself and cause condemnation from society. - Awareness of actions . In most cases (except for cases where the offender is declared incompetent), the offender is fully aware that his actions are illegal.

Causes of delinquent behavior in adolescents

Adolescence is characterized by a desire for independence, social activity and misunderstanding, inability to take responsibility for one’s actions. Due to their unformed personality, girls and boys easily succumb to outside influence, copy behavior, imitate, and are carried away by the idea of risk, adventure, and quick gain. The greatest increase in antisocial and illegal actions is observed from 14 to 20-25 years. Among the reasons that provoke delinquent behavior in adolescents are:

- Microsocial conditions.

The asocial and antisocial environment of adolescents shapes appropriate behavior. Factors of delinquency are alcoholism, drug addiction of parents, intra-family conflicts, neglect, demonstration of violence, psychological cruelty, lack of parental love, care, acute psychological trauma (death/change of parent, rape). - Macrosocial conditions.

An increase in the crime rate occurs under unfavorable economic conditions, political instability, weak government, imperfect legislation, and social cataclysms. A low standard of living and a decline in morality provoke delinquency as a way to achieve goals (obtaining material benefits, social status). - Constitutional prerequisites.

Sociopathy is formed on the basis of high basal aggression and reduced reactivity of the nervous system. These features are manifested by a craving for thrills, insufficient plasticity - the ability to adopt socially acceptable behavior. The intensity and uncontrollability of desires provokes episodes of theft and attacks. - Features of the motivational sphere.

The direction of adolescent behavior is explained by the diversity, inconsistency, uncertainty, and instability of motives. The basis of delinquent actions is often the desire to appear brave, to show off, to gain respect from peers, to acquire material wealth, to take revenge, to experience an adventure. Misdeeds are often situational, and there is no clear understanding of the boundaries of social acceptability.

Pathogenesis

Delinquent behavior of adolescents arises on the basis of an internal conflict between desires, goals and the need to comply with the requirements of society. The inability to correctly assess the situation, put oneself in the place of another, and be responsible for actions becomes the basis for the consolidation of delinquency. Intrapersonal conflict is smoothed out by justifying one’s actions by circumstances, condemning others, distorting the assessment of the harm caused, and denying the victim’s status as a victim. Legal ignorance of adolescents and confidence in impunity increase the likelihood of criminal behavior. On the other hand, deviation is a private manifestation of social interactions in society. The pattern of behavior exists outside of the adolescent's personality.

Classification

The variety of social norms forms a large number of classifications of delinquent behavior. In the socio-legal sector, the division of illegal actions into violent and selfish is widespread. In psychology, pedagogy, and medicine, the degree of severity of delinquency and the nature of a teenager’s personal deformations are taken into account. There are three types of behavior:

- Consistently criminal.

Criminal acts are manifestations of habitual behavior. The teenager is dominated by asocial views, attitudes and values. - Situational criminogenic.

Crimes are committed under the influence of external circumstances and are unsystematic (from case to case). Teenagers are driven, easily carried away, with an unstable value system. - Situational.

An unfavorable combination of circumstances leads to violation of moral standards and the commission of administrative offenses. Manifestations are isolated.

The concept of a delinquent

A delinquent is a person whose actions are antisocial and illegal.

The actions of this subject involve a violation of legal norms.

Inappropriate behavior of a delinquent leads to legal consequences for him.

A delinquent may be an adult or a teenager .

Specialists pay special attention to the problem of deviant behavior in adolescents, since these representatives of society, due to the age-related characteristics of their psyche, are at risk.

Timely assistance from parents, teachers, and representatives of public organizations can prevent the further development of a child’s criminal personality.

Symptoms of delinquent behavior in adolescents

The lack of need to learn new things, self-realization, achieving goals and the predominance of primitive tendencies (sex, food, alcohol) determine the behavior of adolescents. The circle of friends is usually narrowed, acquaintances are limited to the place of residence - a yard, a block, a district. Free time is wasted on visiting “parties” and “gatherings” of the company. Delinquent teenagers do not go to sports clubs, although they often have good health and physical development. They are not interested in classes in clubs and creative studios. Relationships with classmates do not work out.

Delinquents have a negative attitude towards learning. Underachievement increases from primary school onwards and is aggravated by dysfunctional relationships with teachers and peers. Absenteeism and refusal to attend school are common. Leisure is meaningless and primitive. Teenagers prefer to consume light information that does not require intellectual processing and provokes strong emotions - comedies, action films, horror, cartoons, humorous and erotic photos, pictures. Superficial social contacts are focused on exchanging opinions about what was viewed. The growing need for thrills contributes to passion for gambling, alcohol, and drugs.

Specific manifestations of delinquency are administrative offenses - failure to comply with traffic rules, foul language, obscene language, insults, humiliation of others, drinking alcohol, appearing intoxicated in public places. Criminal behavior is realized through crimes. Among teenagers, the most common property damage is arson and vandalism. Thefts, car thefts, fraud, drug distribution, murder, and violence are less common. A crime entails punishment - community service, a fine, arrest, imprisonment.

Difference from deviant

How does deviant behavior differ from delinquent behavior?

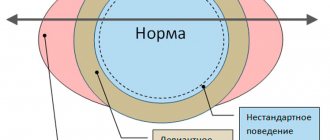

Deviant behavior is a violation of the norms, foundations and rules existing in society, which does not entail a violation of the law and the onset of legal consequences.

For example, a form of deviant behavior is the systematic consumption of alcoholic beverages by a minor.

Delinquent behavior, in contrast to deviant behavior, manifests itself in the commission of not only antisocial acts, but also offenses for which appropriate punishment is imposed (fine, imprisonment). For example, violating traffic rules.

In other words, deviant behavior is the first type of delinquent behavior - disciplinary offenses. Most often, teenagers are prone to exhibiting deviant behavior .

It can easily develop into delinquent behavior if parents, teachers, and law enforcement officials do not intervene in time.

Complications

A complication of delinquent behavior in adolescents is a lag in intellectual and personal development. Lack of cognitive interest, conflicts with teachers, absenteeism from school lead to a decrease in memory, thinking, attention, and limited horizons. Pedagogical neglect is often complemented by organic brain damage associated with alcohol, drug intoxication, and traumatic brain injuries. Personal development is hampered and distorted, since there is no stable system of values, there is no diversity of relationships. Adolescents do not have the need to change themselves or improve their adaptive capabilities.

Causes

As a rule, the formation of delinquent behavior occurs under the influence of not one factor, but a combination of them .

The preconditions that contribute to the emergence of problems appear in most cases already in childhood.

A child growing up in an unfavorable environment is more likely to exhibit antisocial behavior in the future than a child growing up in a supportive environment.

The main causes of problems:

- physical, psychological violence in the family;

- conflicts between parents;

- lack of attention to children from parents, ignoring their interests;

- lack of discipline in the family, or the presence of excessively strict discipline;

- alcohol and drug abuse in adults;

- committing illegal acts by adults.

How does the Oedipus complex manifest itself in adult men? Find out about this from our article.

Diagnostics

Medical diagnosis of delinquent behavior of adolescents is carried out by a psychiatrist or psychologist. In addition to clinical collection of material, there are various questionnaires, observation cards, and interview plans. The data is supplemented by the characteristics of teachers, district police officers, and extracts from the outpatient records of doctors of narrow specialties. The teenager and parents take part in the diagnostic process. The examination scheme is as follows:

- Conversation, observation.

The psychiatrist collects anamnesis, asks about the characteristics of intrafamily interaction, the teenager’s antisocial and illegal actions, their onset, periodicity, and frequency. Evaluates the productivity of the contact, the characteristics of the patient’s behavior at the appointment (adequacy, aggressiveness, emotional instability). - Questioning.

Questions of specialized methods determine deviations in the moral sphere, a tendency to illegal acts, addictions, affective, aggressive behavior, deviations in the sexual sphere. The results may be deliberately distorted by the teenager. The test “Determination of propensity for deviant behavior”, “Propensity for deviant behavior” is used. - Psychological testing.

Personality questionnaires and projective methods are used for a deeper study of the emotional-volitional sphere and character traits of a teenager. The results are used to make a diagnosis and select psychotherapy techniques. The Pathocharacterological Diagnostic Questionnaire (PDQ), the Multilateral Personality Study Methodology (MMIL), the Hand Test, and the Rosenzweig Frustration Test are used.

It is important to differentiate between delinquent and deviant behavior. A distinctive feature of both types of disorders is that actions contradict the rules accepted in society. But with deviation, actions are immoral, immoral, and with delinquency they cause moral, physical and material harm to an individual or society.

12.4. Motivation for criminal (delinquent) behavior

About the criminal (delinquent, from the Latin delinquens

- offender) behavior, as a type of deviant behavior, is said when the subject chooses an illegal way to satisfy needs, desires, relieve mental tension - uses physical force or weapons with the aim of causing injury, mutilation or deprivation of life. In this case, criminal intent turns aggressive behavior into a crime.

The motivation for criminal behavior can reflect not only aggression, but also other illegal acts: accepting a bribe, theft, etc. Therefore, it has independent significance, attracting more and more attention from lawyers in recent years. Evidence of this is a collective study by lawyers and psychologists, compiled in the form of a monograph (“Criminal Motivation”). This work leaves an ambivalent impression. On the one hand, criminologists, whose professional task is to clarify the motives of a crime, express certain common-sense and, for psychologists, even advanced thoughts (obviously because they are closer to real life than the latter, who talk about motives in an abstract, detached manner), and on the other On the other hand, among them there is also no common understanding of motivation and motives, especially since they rely on the work of psychologists.

One of the leading criminologists, Academician V. N. Kudryavtsev (1978), understands the motivation of criminal behavior as the process of forming the motive for a crime,

its development and formalization, and then its implementation in actual criminal actions.

He believes that motivation must be distinguished from the mechanism

of criminal behavior both in scope and in the content of these concepts. Motivation, from his point of view, does not cover the entire mechanism, because the latter includes the implementation of the decision made and self-control (with which it is difficult to disagree). But V.N. Kudryavtsev does not include in the motivation and assessment of the situation by the subject, and his anticipation of the consequences of his actions, and decision-making. It turns out that a person, when committing a crime, acts as if blindly.

V.V. Luneev (1980) believes that all of the listed elements are included in motivation:

…

Being a dynamic process, motivation... is associated with all elements of criminal behavior: the actualization of needs, the emergence and formation of a motive, goal setting, the choice of ways to achieve a goal, predicting possible results, decision making. [27]

However, V.V. Luneev included in the motivation an analysis of the consequences that have occurred, and even repentance and the development of a protective motive, which does not apply to motivation as a process of forming a crime plan. Thus, his understanding of motivation is too broad, while V.N. Kudryavtsev’s is narrowed.

There are also contradictions in criminologists’ understanding of motive. Most authors understand motive as an impulse: “a conscious impulse (desire) to commit a specific purposeful act (an act of will), representing a social danger and provided for by criminal law as a crime” (S. A. Tararukhin, 1977), “an internal impulse that causes the person has the determination to commit a crime”, “the motivation that guided the person in committing the crime” (B. S. Volkov, 1982). True, motivation for criminologists is more likely the basis of an action, and not an energetic impulse that forces the subject to be active. Thus, K. E. Igoshev (1974) understands the motive of criminal behavior as an impulse formed under the influence of the social environment and life experience of the individual, which is the internal direct cause of criminal activity and expresses a personal attitude

to what the criminal activity is aimed at.

Emphasizing that the motive of criminal behavior is an incentive, V. N. Kudryavtsev at the same time notes that the motive of a crime can only be discussed when such elements of criminal behavior have already appeared or are being formed, such as an object or subject of influence, a goal or a means of achieving a criminal result. At the same time, it is not specified whether we are talking about a imagined or a real goal and the means of achieving it. If the latter is true (and the following phrase by V.N. Kudryavtsev suggests such an understanding: “... There is no reason to see criminal motivation in the very distorted needs or interests, views or feelings of a person who has not committed anything illegal. From the deformation of these elements of the personality to the actual act there may be a fairly large distance") [28], then only one conclusion follows: there is no crime - which means there is no criminal intent, motive. However, an unfulfilled intention does not mean that this intention did not exist. It is obvious that the author, wittingly or unwittingly, identifies criminal behavior with a criminal motive, which, in the event of a delay or failure to achieve the goal at the moment, turns into a motivational attitude. A person is not yet a criminal (and may never become one), but is already socially dangerous because he has the determination (intention) to commit a crime. Therefore, I. I. Karpets’s (1969) criticism of the views of Western criminologists who talk about a “dangerous state” of an individual does not look very convincing.

Understanding this is important for the prevention of crimes, which should consist not only in eliminating the conditions for their commission, but also in changing the views and attitudes of the individual, i.e. in his education and re-education. V.N. Kudryavtsev obviously agrees with this, since he writes that knowledge of the motives of criminal behavior makes it easier to plan individual prevention measures and predict the subject’s future behavior, gives an idea of the content, depth and degree of stability of his antisocial views; in some cases, knowledge of motives makes it possible to judge the conditions for the formation of personality, as well as the situation in which criminal intent arose.

Thus, if for criminal law there is only one aspect - whether a crime has been committed or not, then for law enforcement agencies and pedagogy this is not enough: it is necessary to identify intentions, personality traits that can lead to the emergence of motives and motivational attitudes of criminal behavior.

The lack of established views on the essence and structure of the motive leads V. N. Kudryavtsev to obvious contradictions. He argues that one can speak about the motive of a crime only when the object of influence, the goal and the means of achieving a criminal result have already appeared or are being formed, and immediately writes that such an extreme should not be allowed in which precisely these elements are included in the motive, otherwise it begins to cover the entire subjective side of an intentional crime. But isn’t it reasonable to consider the entire subjective side, that is, the entire structure of the motive?

Due to giving the crime only a legal basis, V. N. Kudryavtsev concludes that the same motive, depending on the situation, can be an incentive for both a crime and a legal action. But if there is an intention to commit a criminal act (as the final stage of motive formation), then this motive cannot but be criminal.

Thus, works on the motivation of criminal behavior reflect the general situation of the problem of motivation that exists in psychological science, with all its contradictions and ambiguities. Studying motives, criminologists would like to know about the experiences and feelings of the person who committed the crime, about his needs and interests, ideals, attitudes and beliefs, goals and means of achieving them, about planning the result, i.e. everything that served as the basis for the criminal act . And this is only possible if the motive for criminal behavior is considered (which has not yet been done) as a complex multicomponent psychological formation, and the process of its formation as a dynamic, staged one.

At the same time, one cannot fail to note the statements of criminologists about motive that deserve attention and sometimes advance the thoughts of psychologists. Thus, V.V. Luneev says that the motive, along with its most important function of motivation, also performs the regulatory function of a filter

when the subject selects and evaluates what promotes or counteracts the satisfaction of an actual need. He also considers another function of motive - reflective, which psychologists do not directly talk about (although there are similar statements, for example, by K. K. Platonov). Criminologists can also add a clear idea that motivation is the process of forming a motive, that is, a motive is the result of this process (V.D. Filimonov, 1981; V.N. Kudryavtsev).

Undoubtedly positive in the views of criminologists on motive is the position that the motivation for a crime reflects not only and not so much this or that criminogenic situation in which it is committed, but rather all the previous negative influences of the social environment that have formed a personality with an antisocial orientation, or rather, deformed the motivational sphere personality. Consequently, the time limits for reflecting criminogenic influences in the motivation for crime cannot be limited to a specific situation. Here V.V. Luneev quite clearly expressed the idea that by studying the structure of a motive, we thereby study the history of personality formation, its structure. There is a certain parallelism between the dominant motives of the offender and his social roles and connections, so personality traits are reflected in the characteristics of the motives for criminal behavior in 70–75% of cases.

V. B. Golitsyn (1985) revealed that delinquents are characterized by the dominance of needs for subsistence and insufficient formation of the needs of development, cognition, work, and interpersonal communication.

Based on the severity of certain needs and characteristics, D.I. Feldshtein (1993) divides adolescents with an antisocial personality into five groups. To the first group

includes teenagers who took the path of crime by accident.

They are weak-willed and easily influenced by their environment. Their needs are prosocial and are not in themselves the cause of their antisocial behavior. The second group

includes adolescents with slightly deformed needs.

They are easily suggestible, frivolous, and curry favor with their comrades. The third group

of adolescents is characterized by a conflict between deformed and prosocial needs, interests, and attitudes.

The correct moral views they had did not become convictions. They are characterized by an egoistic desire to satisfy their needs, which leads to antisocial actions. The fourth group

consists of teenagers with deformed needs and base aspirations, imitating those juvenile delinquents who have a stable set of immoral needs and openly antisocial attitudes and views.

They commit offenses mainly situationally, as a result of a motive that spontaneously arises against the background of the general orientation of the individual. The fifth group

includes adolescents with a stable complex of socially negative, abnormal, immoral, and primitive needs. Selfishness, indifference to the experiences of others, desire for consumer pastime, and aggressiveness are combined with deliberately committed offenses.

An important question for criminologists is at what stage of motivation criminologically significant personality deviations begin to appear. And here the positions expressed by them are not always convincing. It is stated, for example, that there are no needs, motives and partially goals characteristic only of criminal behavior, just as there are no antisocial needs and motives (V.N. Kudryavtsev, V.V. Luneev), and authors who hold the opposite point of view are criticized on the basis that the social assessment of a motive depends not on its abstract content, but on the system of social relations in which it is included and which social relations it is opposed to. It is argued that needs and motives cannot be correctly assessed from the point of view of social usefulness or harmfulness, since the latter is revealed through the goal, the means of achieving it and the resulting consequences, through the subject’s attitude to social values, which he neglects while realizing his desire.

Indeed, the impulse is socially neutral (although this approach is also criticized), since both a crime and a noble deed can be committed for the same outwardly similar motive. Revenge on a neighbor for an insult, realized in causing bodily harm, is antisocial, and revenge on an enemy of the Motherland is sacred. But motive, if understood as the basis of an action, cannot be neutral. This misconception arose among criminologists because they understand motive too narrowly, not including precisely those elements that make a person’s behavior antisocial and criminal: a means to achieve a goal, anticipation of consequences, attitude to social values. It is in the example of motivation for criminal behavior that one can clearly see how the existing understanding of motive in psychology hinders the understanding of the problem of behavior as a whole and causes unnecessary discussions.

Understanding motive as the basis for an action (for what purpose, for what purpose) gives grounds to talk about antisocial motives in view of the antisocial orientation of the subject’s plan.

An antisocial plan becomes such, of course, in connection with social relations, the morality of society, which gives a moral assessment (and legal authorities also establish a legal assessment) of this or that act. It is not the needs themselves that are criminal, and many goals taken individually; other components of the motive associated with the “internal filter” block give them a criminal connotation. And the main criminal “load” in it is carried by the component associated with moral control. It is the deformations and distortions of this component of the personality structure that lead to criminal behavior, and not self-interest, envy, revenge, discontent, resentment and bitterness, attributed by V.V. Luneev to the motives of crimes. There may be a long distance between the occurrence of these conditions and the intention to commit a crime. What is criminal is not the desire of a hungry person to get food, or of an angry person to respond to an offender, but the antisocial and illegal ways in which they want to do this; therefore, both needs and external circumstances are “to blame” for the content of the crime only insofar as they facilitated the formation of the intention to satisfy the need, but no more. If there were no need or corresponding situation, there would be no crime; but with the same success one can blame the victim for committing a crime: if she had not appeared in this place and at this time, this crime would not have occurred.

Thus, most of the components that form the structure of the motive of a crime (criminal action) are not criminal. However, since a person chooses criminal paths and means to satisfy a need and achieve a goal, the motive as a whole, like the plan and intention, acquires a criminal character.

Age-related characteristics of motivation for criminal behavior.

V.V. Luneev (1986) provides data that show that the motives for criminal behavior among people of different ages differ significantly. Adolescents aged 14–16 years are characterized by two types of criminal motivation: selfish, the share of which reaches more than 50%, and violent-egoistic, the share of which is 40%. The intermediate form (selfish-violent) is most often committed when the motivation of self-affirmation dominates.

Specific reasons for the criminal behavior of adolescents are: the desire to have fun, to show strength, courage, dexterity; to establish oneself in the eyes of peers, the desire for something special, for sweets, prestigious things. Therefore, three quarters of adolescent crimes are situational and impulsive in nature.

The criminal behavior of 16-17 year olds is similar in many aspects to that of adolescents. However, there are also differences. The number of crimes for mercenary motives is decreasing (up to 40%). Motivation seems to “grow up” and become more diverse. The motives for criminal behavior in people of this age are (in descending order of frequency of manifestation): self-interest, hooligan motives, obtaining funds for alcohol and drugs, revenge and bitterness, solidarity with others, mischief, to obtain funds for sweets, to show one’s strength and courage, establish yourself in the eyes of others, etc.

The criminal motivation of young people aged 18–24 years is characterized by a greater connection not with the specific situation and mental state of the subject, but with the orientation of the individual, his views. The proportion of violent-egoistic motives increases and the number of “childish” motives decreases (the desire to gain authority from peers, imitation of others, wanted adventure, under duress). At the same time, the number of cases where the criminal cannot clearly determine the motive for his act is increasing.

In adulthood, the proportion of violent-egoistic motivation decreases. Selfish motivation, motivation of profit, benefit, envy comes first. The nature of violent-egoistic motivation is changing: hooligan impulses give way to motives associated with bitterness, jealousy, and revenge. The situation plays less and less of a role.

Under addictive behavior

- addiction) understand the abuse of one or more chemical substances, occurring against the background of an altered state of consciousness.

As you know, bad habits include drinking alcohol, drugs and smoking.

Motives for drinking alcohol.

In more than a third of cases, the main motives for adolescents and young men to start drinking alcohol are traditions and customs, the observance of which serves as a means of inclusion in the reference group. Teenagers and young men do not come to company to drink, but drink to be in company. At the same time, in most cases, the motives for drinking alcohol are not yet sufficiently understood by adolescents.

Motives for starting drug use.

The main reason for starting drug use is curiosity (in 50% of cases). Less often, drug addicts surveyed answer that they were seduced, and very rarely that they wanted a high or that they started using drugs because of fashion. Many cannot indicate the true reason and therefore answer that they were offered.

In adults, the reason for using alcohol or drugs may be the desire to resolve a conflict, to eliminate the tension between the desired goal and the means of achieving it (or rather, the lack of these means), i.e., what is referred to in sociology as anomie. One of the functions of alcohol or drugs may be to temporarily “rescue” a person from the tensions of everyday existence with its apparent or actually insoluble conflicts. The thirst for such “freedom” leads to addiction to alcohol and drugs and can become the cause of self-destructive behavior and take the form of illness.

A study by N.N. Tolstykh and S.A. Kulakov (1989) showed that early alcoholism and substance abuse lead to changes in the motivational sphere of young men aged 15–17 years. Their time perspective narrows. The distribution of objects for satisfying their needs occurs in the “near future” (today, within a week, a month) and in the “current period”, not exceeding 1–2 years (see Fig. 12.2).

Young men with addictive tendencies have a reduced need for communication, but an increased motive for personal autonomy, with their own personality, with the “I” (see Fig. 12.3).

The desire to recover from this disease (in particular, alcohol addiction) is determined by many reasons. According to K. A. Yufereva, this is, first of all, a deterioration in well-being (in 83% of those examined) and memories of periods of sobriety (in 85%); then, in order of importance, come: “a feeling of emptiness in life” (in 70%), deterioration in relationships with family (in 68%), decreased performance (in 65%), deterioration in relationships at work and the threat of dismissal (in 60%), deterioration of financial situation (60%). Much less frequently mentioned are fear for one’s life (in 47% of cases), exacerbation of diseases (in 37%), decreased sexual capabilities (in 12%), and conflicts with the police (in 7%).

Motives for initiation of smoking among adolescents and young men.

According to V. A. Khudik (1993), students under 13 years of age say (in descending order of importance) simple pampering, curiosity, the desire to appear grown-up, and pleasant sensations as the reasons for starting to smoke. After 13 years, these reasons are joined by factors of group pressure: reluctance to be a “black sheep,” the influence of comrades, fear of rejection by smoking comrades, fashion, imitation of the ideal. The desire to lose weight is also indicated.

Treatment of delinquent behavior in adolescents

Treatment is complex and involves the participation of a psychiatrist, psychotherapist, psychologist, social worker, and parents. Behavior correction is based on the development of positive personality traits and the elimination of distorted perceptions of social situations. Adaptation is focused on crowding out dangerous actions and stimulating socially useful activity. The following methods of helping teenagers are common:

- Cognitive behavioral psychotherapy.

The sessions are aimed at correcting the emotional state, destructive thoughts and ideas regarding one’s own “I”, relationships in social groups. The psychotherapist teaches the teenager reflexive thinking and develops skills of socially effective behavior. - Family psychotherapy.

Classes with teenagers and parents are conducted in the form of games and trainings. The goal is to develop and consolidate ways of productive interaction. Family members learn to communicate, collaborate, and plan leisure time. At the same time, behavioral patterns that support delinquency are identified and corrected. - Creative therapy.

A promising direction in working with delinquent adolescents is art therapy. Creative activities allow you to openly express emotions and thoughts, objectively evaluate them, and overcome deviations in the motivational-volitional and emotional sphere. Drawing, dancing, modeling, and participation in theatrical performances are considered as an alternative way to spend free time. - Drug treatment.

The use of medications is an additional method necessary for severe emotional abnormalities and psychopathological disorders. The psychiatrist prescribes sedatives, antidepressants, and antipsychotics.

Prognosis and prevention

The prognosis for delinquent behavior in adolescents is favorable with comprehensive pedagogical, psychological and medical assistance. A positive outcome is determined in 50-70% of cases. Prevention should begin from a very early age. It is important to devote time and effort to the upbringing and mental development of the child, to organize varied and useful leisure time, to support hobbies in sports and creativity. It is necessary to exclude situations of idleness, but maintain the possibility of passive rest. In a relationship, you need to show respect to the child, praise and encourage him for his achievements, building positive self-esteem. Success stimulates interest and passion for activities. Correct values and moral foundations, embedded in a child before adolescence, make it possible to resist negative information received from various sources.

LiveJournal

Control mechanisms and strategies

The state can use certain mechanisms and strategies to change the situation and prevent its aggravation. There is a fundamental difference in the application of mechanisms and strategies.

Mechanisms are certain, specific methods of influence that are coercive or mandatory.

Mechanisms that society should apply to reduce the number of manifestations of delinquent behavior:

- strengthening the system of punishments for committed acts;

- exercising indirect control over individuals at risk through their introduction into groups of law-abiding individuals.

Strategies are general plans of action over a long period of time aimed at achieving a goal. Strategies to reduce the number of delinquents in society can be as follows:

- Raising the general cultural level of the nation . The higher the level of spiritual development of a person, the less likely it is that he will commit an antisocial act.

- Improving the quality of life of the population , as a result of which the level of material well-being of the nation will increase, and the need to commit illegal actions to obtain various benefits will decrease.

- Legalization of forms of behavior that are asocial, but do not entail legal consequences: vagrancy, prostitution, homosexuality.

The ability to act without cover will give representatives of these social groups and subcultures full rights in society. This will save them from the need to break the law in an effort to hide their inclinations and interests from society. - Development of a comprehensive support system: drug treatment, psychological, etc. Support should be aimed at facilitating socialization and adaptation in society for citizens with various problems.