Thinking

The accumulation of knowledge does not lead to the development of thinking; it is formed only in active practical and cognitive activity. The development of a preschooler’s thinking goes through 3 stages and represents a complex interrelation of various forms of thinking:

- Visual-effective thinking (3–5 years). The main feature is the inextricable connection of thought processes with practical actions that transform the cognizable object. To think, you need to act with objects. For example, a child spins a toy, presses all the buttons, tries to open it, thus he “experiments and learns with his hands.” In the process of repeated actions with objects (and over a couple of years, hundreds and thousands of different objects will pass through the child’s hands), the child identifies their hidden characteristics and internal connections. Practical actions with objects become a means of understanding reality and form thinking.

- Visual-figurative thinking (4–6 years old) - the child begins to think not with specific objects with the help of his hands, but with their images and ideas, well imagining such objects. The child learns to cognize and solve problems in his mind, relying on his figurative ideas about objects, whereas before this he could only through practical actions. Now, in order for the child to find out which figure fits which hole, he does not need to insert them alternately, he can do this in his mind and quite quickly.

It is worth considering that a child is not always able to come to the correct answer through visual-figurative thinking. His thinking may be strongly influenced by perception. If you show a child two absolutely identical and equal-in-volume balls of dough, and then in front of his eyes, turn one of the balls into a cake and ask where there is more dough, then the child will often declare that the amount of dough in the cake has increased. This thinking error is due to the fact that the child does not yet have the concept of volume and knowledge of other metric measurements. Visual models in which the properties and relationships of objects are reproduced are the most important condition for the formation of internal mental activity.

For the emergence of imaginative thinking, imitation of an adult is also important. By reproducing the actions of an adult, the child builds internal models of actions that he plays out in role-playing games.

3. Logical thinking - begins to take shape towards the end of preschool age (about 7 years) and develops over many years, allowing the child to master the principles of logic. Such thinking is characterized by the fact that as a result the child operates with rather abstract categories and establishes various relationships that are not presented in visual form. However, at first, it is easier for the child to establish cause-and-effect relationships if a specific object is right in front of him and the changes occurring with it can be directly observed. Gradually he moves to thinking that is more abstracted from the current situation.

Why do you need drawing lessons?

Some parents focus entirely on how well their child is doing in math, reading, and writing. They are in a hurry to wean the younger schoolchildren from games and do not pay attention to drawing, modeling, and design. Often such parents do not understand at all why drawing classes are needed at school. “Anyway, my child does not have the ability for this and he will never become an artist,” they reason.

However, drawing lessons (like other “children’s” activities) are needed not only for the child to master skills in this area. They also have a much more general meaning. Such activities develop imaginative thinking, the ability to imagine various situations in the mind. This is a necessary condition for harmonious mental development.

Children's experimentation

Sometimes another type of child’s thinking is identified - child experimentation. It represents the unity of visual-effective and visual-figurative thinking, and is aimed at knowing the properties and connections of objects.

Such thinking takes the form of experimenting with a phenomenon: the child causes or stops the phenomenon, changes it in one direction or another. In the process of such actions, the child receives new, sometimes unexpected information, which often leads to a change in ideas about the object. For example, a child puts a wooden boat in a stream and sees how it floats, then he takes his toy boat made of iron and sees how it goes to the bottom. The child is perplexed, because both toys are boats that should float, but one drowned. Then the child comes to the conclusion that not every boat is capable of sailing and begins to investigate this issue. In this experimentation, the moment of self-development is clearly presented: the use and transformation of an object/phenomenon reveals its new properties to the child, which, in turn, allow them to make guesses and bring them to life.

Experimentation encourages a child's curiosity and initiative, independence, flexibility of thinking, courage, and stimulates the search for new solutions and creativity. Independent experimentation gives the child the opportunity to try different ways of doing things, while removing the fear of making a mistake (since there is no right option). The ability to be surprised by new things, to make your own guesses, to ask yourself and others questions is more important in the development of thinking than the reproduction of ready-made patterns of action and the assimilation of knowledge given by adults. The role of an adult in this process comes down to creating special objects and situations that stimulate cognitive activity and experimentation.

Knowledge formalism

Formal knowledge is the kind of knowledge that a child cannot apply in practice. For example, with formal knowledge of the multiplication table, a student cannot solve a problem like: “If each of four boys has three balls, then how many balls do they have together?”

One of the most important reasons leading to formalism is the underdevelopment of imaginative thinking. In this case, excessive rationality easily arises. Logical reasoning that is not based on ideas about reality may look correct on the surface, but in essence it is meaningless. Such problems often arise in children whose parents began early to teach them to read, write and count, without caring about other aspects of their development.

Phenomena of children's thinking by J. Piaget

At first, a child’s thinking is extremely imperfect and its main feature is egocentrism - when the child evaluates any situation only from his own position (point of view). What the child perceives seems to him to be the absolute and only possible option. The reason for this is insufficient separation between the Self and external reality.

An excellent example of egocentrism is the well-known test about brothers, where an adult asks a child:

- You have brothers? - Arthur. - Does he have a brother? - No. – How many brothers do you have in your family? - Two. - How many brothers do you have? - One. - Does he have brothers? - No, absolutely not.

The child does not realize that he may not be the “central” object, and therefore does not realize that his brother has brothers.

Jean Piaget identified other phenomena of children's thinking, which are based on egocentrism:

Animism is the attribution of animation to inanimate objects. Piaget reports the following conversation with a boy:

– Is the sun alive? - Alive. - Why? - It gives light. – Is the candle alive? – Alive, because it gives light. She is alive when she gives light, but not alive when she does not give it.

Artificialism is the understanding of natural phenomena by analogy with human activity or as created by man.

– What does the sun do when there are clouds and rain? – It is leaving due to bad weather. - Why? - Because it doesn't want to get caught in the rain.

Realism is the tendency to consider objects as they appear in their immediate perception. When the moon follows a child while walking, that means it is so. Or a three-year-old child may watch with interest as dad dresses up as Barmaley, but gets scared and cries when the costume and makeup are ready and he sees the terrifying image. Here another feature of children's thinking of this period is manifested: irreversibility, the inability to mentally return to the starting point. In this example, it is impossible to mentally remove the suit and mask from Barmaley and return to the original image of the pope.

Centering is focusing on only one, most noticeable aspect or feature of an object, while ignoring others, i.e. narrowly focused thinking. J. Piaget demonstrated the phenomenon of centering in his experiments on the understanding of conservation. In these experiments, J. Piaget shows that children at the pre-operational stage of thinking development (from 2 to 7 years) do not understand that the important characteristics of objects remain unchanged, despite changes in their appearance. To the problem below, the child will answer: there are more coins in the top row, the top stick is longer, there is more water in one of the glasses, etc. This happens because he is not yet able to correlate several parameters at once - the length of a row of coins with their number, the thickness of sticks with their length, the height and width of glasses with volume.

Conservation tasks developed by J. Piaget Source: [Burke, 2006] With the development of thinking, by the age of 7 the child overcomes egocentrism and most other thinking phenomena, moving to the level of logical thinking.

In general, children's thinking is still far from that of an adult, and it can be difficult for a child to figure out what is reality and what is pretense. For example, can witches really cast a spell on you or that a person can grow wings and fly like in a picture in a book.

Scientific and everyday concepts

At school, the child is taught scientific concepts: “vowel sound”, “consonant sound”, “sum”, “product”, etc. At home he becomes acquainted with the so-called everyday concepts: “furniture”, “clothing”, “day”, “night”. The power of scientific concepts is that they have clear definitions, so that the child knows well “what to do with them.” Their weakness is that they have little connection with children’s everyday life, and that they can, in general, only be used in the classroom. Naturally, the strengths and weaknesses of everyday concepts are opposite.

Gradually, mutual enrichment of these and other concepts occurs. Scientific concepts penetrate into life: it turns out that “amount” is needed if you need to calculate how much purchases in a store will cost. Everyday concepts become clearer: the child begins to apply to them the methods of reasoning that he learned at school. So, on both sides simultaneously, the thinking of a junior schoolchild is developing.

How do books help develop logic in children?

Even when a child cannot read, it is already possible to develop his logic by reading special fairy tales with questions. If a child has a positive attitude towards reading, then you can begin to develop his thinking from the age of 2-3 years. It is worth noting that through folk tales you can convey to your child not only basic logical thinking skills (cause-effect), but also teach him fundamental concepts such as good and evil.

If you use books with pictures, this has a very good effect on the verbal and logical thinking of a child who has developed imaginative thinking. Children compare what they hear with pictures, stimulate their memory and improve their vocabulary.

Children from 3 to 5 years old will be interested in reading riddles and puzzles. Training should be carried out in a playful way. Some people can already read independently by the age of 5, so it will be doubly beneficial for them to work on riddles.

For older children there are special textbooks on logic and collections of problems. Try to solve some of them with your child. Spending time together will bring you closer and give excellent results.

Logical operations

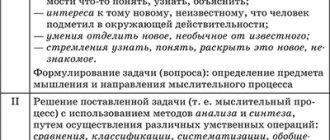

The structure of thinking includes operations, the presence of which in a preschool child implies full mental development. Operations are:

- Comparison is an operation associated with the establishment of similar and distinctive features of any objects. As a result of a logical operation, a classification may appear;

- Analysis is a mental process associated with the division of a complex object into its individual characteristics or parts. The next stage of analysis is comparison;

- Synthesis is a logical operation that combines disparate parts into one whole concept, object;

In psychology, analysis and synthesis are usually viewed as interchangeable operations.

- Abstraction is the mental separation of essential properties, connections, characteristics of an object from non-essential ones. The presence of the ability to perform such an operation indicates the appearance of abstract logical thinking in the baby;

- Generalization - the operation appears as the child’s vocabulary accumulates, and is associated with the imaginary association of phenomena, objects, actions according to significant characteristics;

- Classification is a thinking operation in which the order of things and phenomena is comprehended and divided according to some criterion;

- Concretization is a logical operation by which a preschooler uses the replacement of a word with a concept with a more specific meaning.

Theatrical activities in senior groups of preschool educational institutions